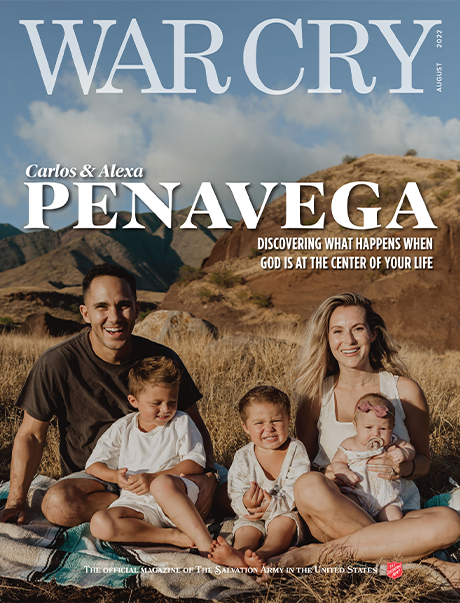

Robin in Chains

Young Prisoners Share Something in Common – Holes in Their Hearts

I started to say “Hello” to the man coming toward me on the sidewalk. But he jolted between the boy beside him and me—a gentle warning in his eyes. Then I saw them—handcuffs and foot shackles. As the plainclothes officer opened the back door of his station wagon, motioning for his teenage prisoner to sit, I noticed the bars between the front and back seats.

My heart slid to the sidewalk. No wonder the kid walked so slowly across the courthouse lawn¸ I thought. I wonder what kinds of holes are in his heart that brought him to this place.

A cement ball caught in my throat as I returned to the store I manage. Since our business is across the street from the courthouse, we often witness young people in handcuffs being escorted to the courtroom. But this was the first time I’d seen one in shackles.

I struggled to keep the tears in check as I told my assistant, Callie, about the teenage prisoner. “My heart breaks every time I see one of those kids. That’s someone’s son, someone’s grandson and God’s precious creation.”

Callie was unmoved. “He’s only getting what he deserves. He broke the law—now he’s paying for it.” Shocked silence hung between us. “Oh, Callie,” I said, “we have no idea what that boy has gone through. I wonder who I’d be if I’d grown up in a home full of beatings, shame or neglect. I might look just like him—wearing shackles and handcuffs.”

That was several years back. A few months ago, at the same courthouse, a jury found a mannerly 17-year-old honor student, whom I’ll call Robin, guilty of second-degree murder. From his early childhood, Robin’s alcoholic mother, Leslie, physically and verbally abused him, often locking him out of the house for days at a time. Neighbors and school officials had called Child Protective Services over thirty times to report her abuse, but authorities labeled each report as unsubstantiated.

In one drunken rage, Leslie reached for a butcher knife, threatening to kill her son. Robin stabbed her instead. Then he turned himself into the police, confessing that he’d taken his mother’s life.

As I followed his trial in the newspaper, my heart shattered a bit more with each new report. A school guidance counselor told of Leslie calling almost daily to ask about Robin, referring to him by a myriad of nasty names, but never his own name. “He was such a fine student,” the counselor said, “and well-liked by all his teachers and peers.”

The defense introduced a recording of Leslie’s voice in a phone call to the school where she threatened to “cut that brat’s legs off with my electric knife, so he won’t be taller than me anymore.” Although the guidance counselor verified that this was indeed Leslie’s voice, the recording was denied as valid evidence, since Leslie did not identify herself by name.

One neighbor testified about seeing Robin sitting on a metal bench outside the trailer he and Leslie shared—a cue that she’d locked him out. The neighbor invited Robin to stay with them—his visits ranging from two nights to an entire week. “Robin never spoke a harsh word against his mother—he was always very polite, even though she called him horrible names and accused him of stealing from her.”

On the day he gave his testimony, Robin sobbed as he told of frequent beatings when Leslie would hit him with her hand, a belt or whatever object was nearby.

“She called me worthless excrement, illegitimate and a thief. It hurt coming from my own mother.” The judge called for a short recess while Robin gained enough composure to continue.

When he took the stand again, Robin’s voice was steady, but his eyes were swollen and red. “Sometimes, my early childhood was fine—we watched TV and played board games. But as my mother’s drinking increased, along with her use of prescription painkillers, she didn’t enjoy my company as much. Her temper got worse as time went on.” He finished his testimony in a choked whisper. “My mother was my best friend. I deeply regret taking her life. But it was either her or me that day.”

When I read that, I prayed for a way to help this broken child. A still, small voice whispered, “Take him one of your books.” I’d written a book focusing on laughter and God’s grace. I wasn’t sure the silly stories about my mishaps would help Robin, but I took it to the jail anyway. I included a letter saying, “Please don’t blame God. He gives people free will and we often choose to ignore Him.” I shared my own story of growing up in an alcoholic home and how the Lord had rescued me from a life of sin and rebellion.

Robin wrote back, empathizing with me over my painful childhood. “Since being here, I’ve heard about far worse situations than my own and it breaks my heart to know how so many people suffer. I don’t believe that God has let me down. No, people have. Through it all, though, I forgive them. I’ve lost a lot, but I’ve learned a lot too.

I fear the unknown and it seems as if that’s my next destination, unfortunately.”

While Robin was in jail awaiting his sentence, I wrote him every day and prayed for him constantly. Then the unexpected happened.

Two months before his sentencing date, the judge let Robin out on bail. I was surprised and elated when he popped into my store one day. We sat and talked for nearly two hours—laughing, sharing dreams for the future, visiting as if we’d always known each other.

A friend with an extra bedroom gave Robin a place to stay. Robin attended church and gave his heart to the Lord. He got a job. He earned his driver’s license. Then the judge sentenced him to eight years in prison and refused an appeal to allow parole.

I stood on the sidewalk and watched as my new friend shuffled to the squad car in shackles. There was that cement ball in my throat again. And this time, I didn’t try to keep the tears from flowing as I waved goodbye.

A friend and I visited Robin every month at the minimum-security prison where he was incarcerated. As I looked around the large, table-filled visiting area at in-mates chatting and playing games with their families, I realized how alike these prisoners and I were. The shackles on my soul before I met Jesus were no less binding than those I’d seen on these teenagers. No matter that society didn’t consider my sins crimes. In God’s eyes, my gossip, selfishness and greed had disqualified me for a spot in Heaven as quickly as someone else’s theft or murder—until I repented and surrendered my life to Jesus, and I was set free.

Whenever I’m tempted to judge another’s sin as worse than mine, I remember that it takes only one sin to put me in spiritual prison and only one Savior’s blood to set me free. Then I pray for the teenage prisoners all over the world to find that Savior.

Thanks to the law which allows for time served, Robin’s sentence was reduced and he walked out of prison after serving two years. Thanks to Jesus, his soul is already free.

This article was originally published in the October 2019 issue of The War Cry.